Knowledge for Everyone, Everywhere

Original, research-based, and human-curated articles reaching readers beyond languages, cultures, and borders.

ExploreFeatured Articles

View All Java Technologies

Java TechnologiesOAuth 2.0: Fundamental Concepts, Terminology, and Authorization Flows

In modern web applications, it is critically important for different services and systems to communicate with each other securely. While using a service, there may be situations where, after logging into the relevant system, we also need to access data in another system. Let us imagine that we have a company offering an online photo printing service; after our customers log into our system, they may want to access their photos on Google Drive to select which ones to print. In such scenarios, the OAuth 2.0 protocol emerges as an auxiliary protocol.

OAuth 2.0 is a standard designed for inter-service authorization. In this article, we will examine in detail the fundamental concepts of OAuth 2.0 and its important authorization flows.

What is OAuth 2.0?

The word "Auth" in OAuth is often confused with authentication, but here "auth" means authorization. OAuth 2.0 is designed to allow one service to grant access to another service—it is not used for a user to authenticate their identity.

OAuth was originally created not for a service to authorize a person, but for a service to authorize another service. So why would one service authorize another? Let us explain the answer to this question with a classic example.

OAuth through the Photo Printing System Analogy

Let us consider a website offering a photo printing service.

Users can place print orders by uploading photos to the system. However, having each user upload their photos one by one from their computer both makes the user experience difficult, increases infrastructure costs, and creates security risks.

Today, most users no longer store their photos on local computers, but rather on cloud services like Google Drive. At this point, the user asks the following question:

“Can I import my photos from Google Drive directly?”

Such a feature would provide great convenience for the user. However, there is a critical problem here:

The files on Google Drive are protected by Google, and accessing these files requires Google authentication.

So how can our website access the user's photos on Google Drive on behalf of the user, without asking for the user's Google username and password?

Incorrect Approach: Requesting User Credentials

In theory: we might think that we can accomplish this process by asking the user for their Google ID and password. However, considering that users will not share such secret information, we can easily say that this idea cannot go beyond theory.

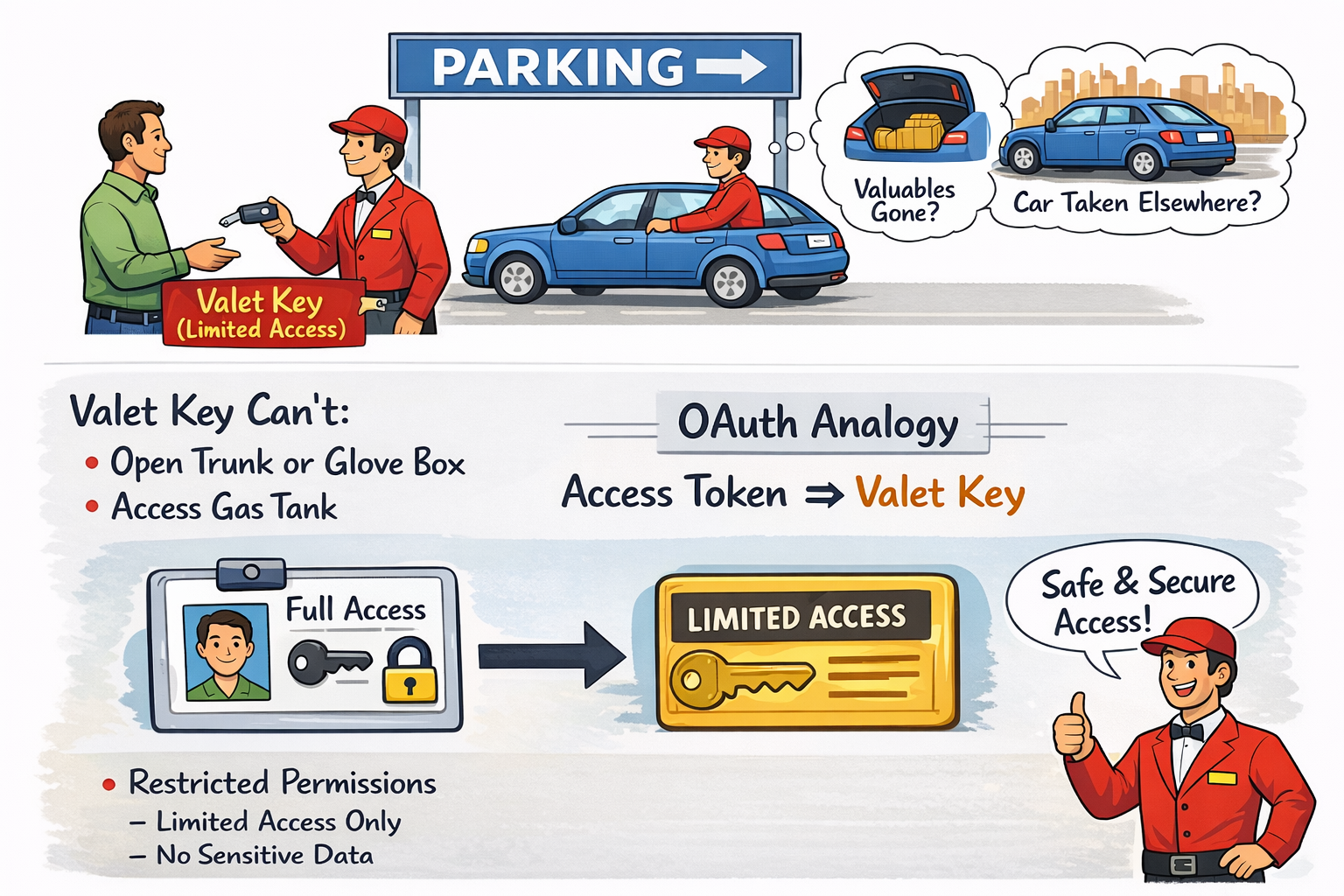

Valet - Key Analogy

There is a very common analogy used to understand OAuth: the valet - key model. A car owner arrives at the parking lot, gets out of the car, and gives the key to the valet, asking them to park the car. The valet takes the key, drives the car to the parking spot, and parks it.

However, some car owners may have concerns when handing over the key to the valet. :) They may worry that a valuable item placed in the trunk or glove compartment could be taken, or that the car could be driven elsewhere...

Some cars come with an additional key for such situations: a valet key. The valet key is like the main car key but has limited access:

• It can start and stop the car

• It cannot open the trunk or glove compartment

• It cannot open the fuel tank

If the car owner has such a key, they feel more comfortable giving it to the valet, knowing that the valet cannot do anything outside the intended purpose with this key.

OAuth works in this way: instead of full credentials, the relevant system is given a 'valet key' (access token) that provides limited access.

How Does OAuth 2.0 Work?

In a web application offering a photo printing service, allowing users to directly access images in their Google Drive accounts provides significant ease of use. However, this scenario introduces a security problem:

Even if the user is logged into both the photo printing service and their Google account, these two systems do not directly trust each other. Each system only recognizes and authenticates the user; for a third-party service to act on behalf of the user, an additional authorization mechanism is required.

At this point, it is not sufficient for the photo printing service to directly request Google for access to the user's files. From Google's perspective, this request is considered an unverified third-party request and is rejected. Google only accepts operations based on the explicit consent of the user when it comes to accessing user data.

The OAuth protocol is designed to solve this security problem. In a system using OAuth, third-party services (in this example, the photo printing service) do not directly request data on behalf of the user; instead, they redirect the authorization process to the user.

The following steps occur in this flow:

1-The photo printing service notifies Google that it wants to access the user's files.

2-Instead of accepting this request directly, Google redirects the user to an authorization screen.

On this screen, the user is clearly presented with:

Which service is requesting access,

What types of permissions are being requested (for example, read-only access),

For what purpose this access will be used

3-If the user approves the request, Google generates an access token for this service.

This access token is considered a credential with limited permissions in the context of OAuth. Full user credentials are not shared; instead, only a temporary authority that can operate within the scope approved by the user is granted. This structure, as in the valet key analogy, restricts access to only the necessary functions.

In the following steps, the photo printing service uses this access token in every request it makes to the Google Drive API. Google verifies the token in the incoming request; if the token is valid and the scope of authority is appropriate, access to the relevant resource is granted. Otherwise, access is denied.

Thanks to this approach:

User passwords are not shared with third-party services,

The scope of access is clearly limited,

The user retains full control over their data.

OAuth 2.0 Terminology

Let us continue to explain the basic terminology you will encounter in OAuth implementations, articles, and documentation through our analogy;

1. Resource

The resource is what all actors in the OAuth flow are trying to access. It is also called the protected resource. In our example, what is the resource? The photos on Google Drive. The entire purpose of the OAuth flow is to provide access to this resource.

2. Resource Owner

The Resource Owner is the person who currently has access to the resource—in other words, the user. The definition in the OAuth specification: "An entity capable of granting access to a protected resource." In the photo printing service example, the service needs access to the resource, and in this case, the access can be granted by the Resource Owner, i.e., the person whose photos are on Google Drive.

3. Resource Server

The Resource Server is the server that hosts the protected resource. In our example, Google Drive is the resource server. The resource server hosts and manages the protected resource.

4. Client

The Client is the application that needs to access the protected resource. It is the application that makes requests to the protected resource on behalf of and with the authorization of the resource owner.

In our example:

• User (the person at the laptop) = Resource Owner

• Google Drive = Resource Server

• Photo printing service = Client

5. Authorization Server (Authorization Server)

The security responsibility lies with the resource server. The resource server is responsible for ensuring the security of the resource. Therefore, the resource server usually comes with an Authorization Server. The authorization server is responsible for ensuring that everyone accessing the resource is authorized. The Authorization Server is the server that issues access tokens to the client.

Note: The Resource Server and Authorization Server can be the same server or separate servers. The specification does not provide detailed information on this, but conceptually they can be considered as two separate areas of responsibility.

OAuth 2.0 Flows

There are flows and implementations designed for OAuth. In this section, we will examine three important flows you need to know.

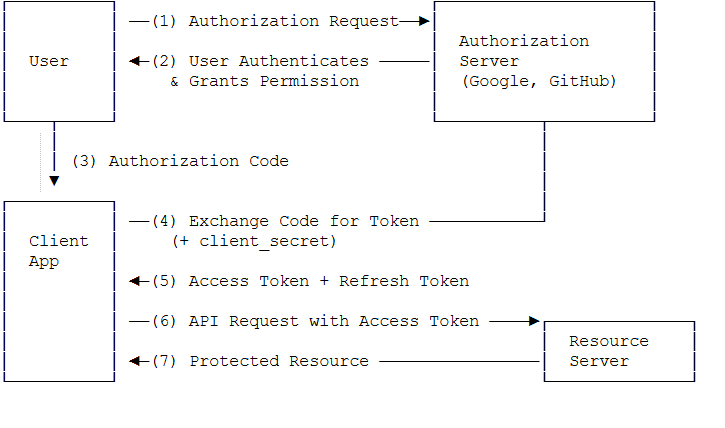

1. Authorization Code Flow

This is the most secure and most recommended OAuth flow. It occurs between the resource owner, client, and authorization server.

The user initiates an action in the client application such as “Sign in with my Google account” / “grant access to my account”.

The client redirects the user to the Authorization Server (usually via browser redirect).

The Authorization Server authenticates the user (shows a login screen) and displays which permissions (scope) are requested.

The user approves the permissions (Consent screen).

The Authorization Server gives the client an authorization code (single-use, short-lived code) → sends it back to the client via redirect_uri.

The client receives this authorization code and makes a request to the Authorization Server in the background (backend-to-backend):

code + client_id + client_secret + redirect_uri

The Authorization Server verifies the code and gives the client the following pair:

access_token (short-lived, used for resource access)

refresh_token (optional, long-lived; used to refresh the access token)

The client now uses the access_token to make requests to the Resource Server (e.g., Google API, Drive, Gmail, etc.).

The Resource Server verifies the token and returns the requested resource (data).

Why is it considered the most secure?

The authorization code does not circulate openly in the browser. The access token and especially the client_secret are used only in the backend. Long-term access can be managed securely with the refresh token.

2. Implicit Flow

The Implicit Flow is similar to the Authorization Code Flow but is somewhat simplified.

The flow works as follows:

Steps 1-4: The first four steps are the same as the Authorization Code Flow. The user makes a request, the client goes to the authorization server, the authorization server obtains user consent.

Step 5: Instead of giving an authorization token and waiting for the client to exchange it for an access token, the authorization server sends the access token directly.

Steps 6-7: The client directly calls the resource server with this access token and obtains the resource.

This flow has a disadvantage: The access token is the only thing needed to access the resource. If someone obtains the access token, they can act as the service and access the resource.

In the Authorization Code Flow, the access token can be exchanged more securely, so it is safer.

Implicit Flow is used in the following situations

:• JavaScript applications (running in the browser)

• When the access token is not expected to be very secure (will be stored in the browser)

• When simple and fast integration is required

In this flow, access tokens should be short-lived.

Implicit Flow is no longer recommended. In modern applications, it is advised to use Authorization Code Flow with PKCE.

3. Client Credentials Flow

This flow is a suitable usage flow for microservices. It is generally used when the client is trusted.

Example: Suppose we have two microservices. Microservice 1 wants to call an API in Microservice 2. Microservice 2 has access to the database. When Microservice 1 calls Microservice 2, it should only be able to access certain APIs, not other APIs and data.

The Client Credentials Flow works as follows:

Step 1: Microservice 1 wants to call an API in Microservice 2.

Step 2: It first makes a call to the OAuth server and provides a special client ID (identifies itself):

Step 3: The OAuth microservice authenticates and prepares the access token required for access to specific resources.

Step 4: Microservice 1 stores this token.

Step 5: Microservice 1 calls Microservice 2. Microservice 2 checks the token.

Step 6: If Microservice 1 tries to access a resource for which the token does not have permission, this request is denied.

Client Credentials Flow is generally preferred for service-to-service authorization in microservice architectures. It ensures that each microservice can access only the data it needs.

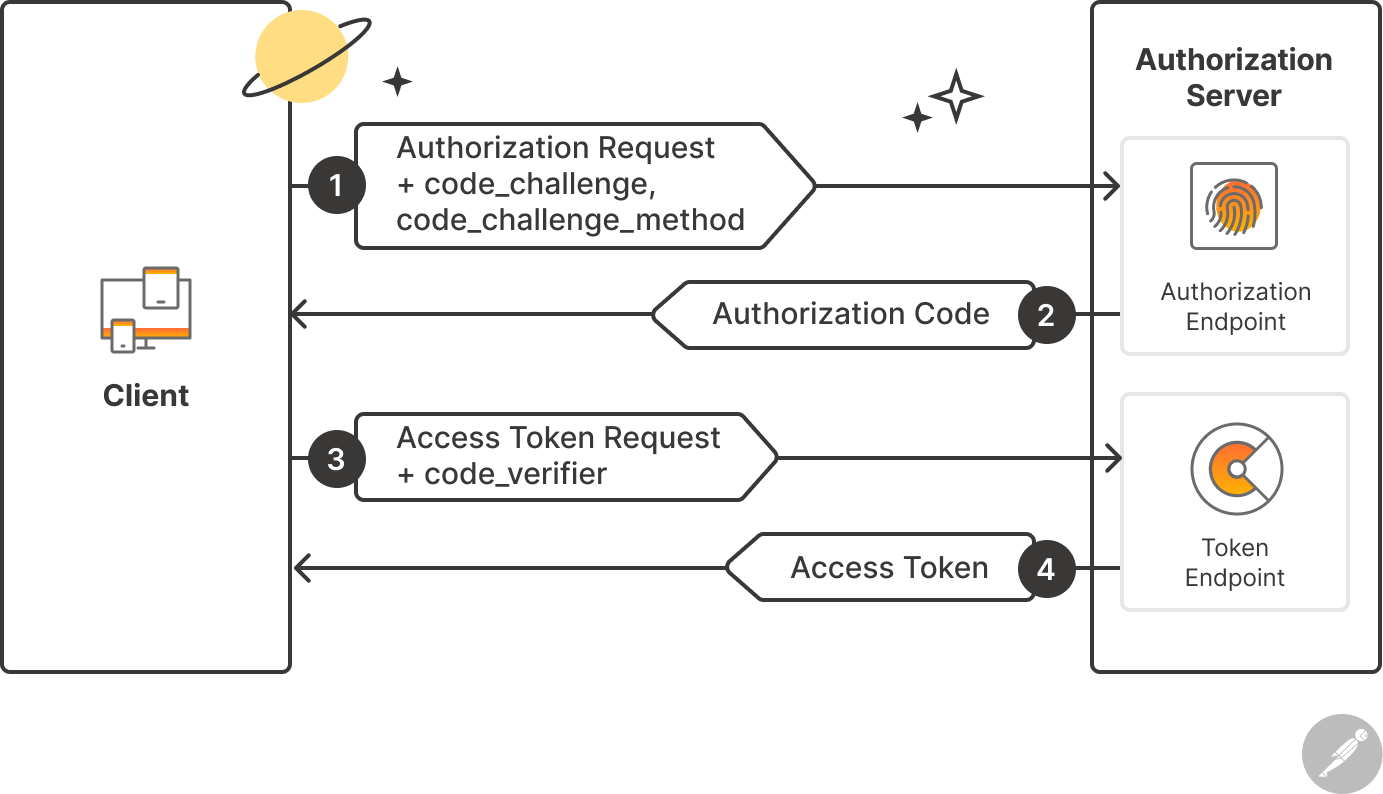

4. PKCE Flow (Proof Key for Code Exchange)

PKCE is an extension of the Authorization Code Flow. It is especially designed for mobile applications and Single Page Applications (SPA). It has replaced the Implicit Flow.

The basic flow of PKCE can be summarized as follows:

1. The client generates a random "code verifier"

2. It sends the hash of this verifier (code challenge) to the authorization server

3. When the authorization code is received, it also sends the original verifier

4. The server verifies that the hash of the verifier matches the previous challenge

In this way, even if the authorization code is intercepted, the access token cannot be obtained without the code verifier.

Access Token Format: JWT

Access tokens must fully contain the granted permissions. They must also be verifiable. Today, the most commonly used access token type is JWT (JSON Web Token). JWT is widely used as the access token format in OAuth 2.0.

JWT consists of three parts:

1. Header: Contains the token type and signing algorithm.

2. Payload: Contains user information and permissions.

3. Signature: Contains a signature that verifies the token has not been altered.

Example of a JWT token structure: eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiIxMjM0NTY3ODkwIiwibmFtZSI6IkpvaG4gRG9lIn0.SflKxwRJSMeKKF2QT4fwpMeJf36POk6yJV_adQssw5c

Advantages of OAuth 2.0

Delegated Access: Enables inter-service access without sharing user credentials.

Open Standard: All services on the internet follow the same set of rules to communicate with each other.

Limited Access: Like a "valet" key, only certain operations can be permitted.

Security: Access tokens can be short-lived and revoked when necessary.

User Control: The user can decide which permissions to grant.

Scope-Based Permissions: Different levels of access permissions can be defined.

Security Considerations

Security points to consider when using OAuth 2.0:

1. State Parameter: Provides protection against CSRF attacks. A unique state value should be sent with each authorization request and verified in the callback

2. HTTPS Requirement: The OAuth flow must always occur over HTTPS. Tokens can be intercepted over HTTP

3. Token Storage: Access tokens must be stored securely. httpOnly cookies should be preferred over localStorage in the browser.

4. Token Lifetime: Access tokens should be short-lived (such as 1 hour) and refreshed with refresh tokens.

5. Scope Minimization: Only the necessary permissions should be requested.

Conclusion

OAuth 2.0 is an indispensable standard for secure inter-service authorization in modern web applications. Valet keyas in the key analogy, instead of sharing full identity information, it uses tokens that provide limited access.

• Resource: The resource to be accessed

• Resource Owner: The owner of the resource (user)

• Resource Server: The server hosting the resource

• Client: The application requesting access to the resource

• Authorization Server: The server issuing the tokens

We examined four important flows:

1. Authorization Code Flow: The most secure, recommended flow

2. Implicit Flow: Old method, no longer recommended

3. Client Credentials Flow: Ideal flow for microservices

4. PKCE Flow: Secure flow for mobile and SPA applications

Thank you for taking the time to read this article.

I hope the content is useful. Don't forget to visit celsushub for new articles.

Sources:

What is OAuth really all about - OAuth tutorial - Java Brains -> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4-416mg6iU

OAuth terminologies and flows explained - OAuth tutorial - Java Brains-> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pZ3Nh8tgTE

Radar Systems

Radar Systems10 - Radar Transmitters and Receivers: Architecture and Technologies

The radar transmitter and receiver are the energy generation and sensing core of the system. The transmitter amplifies the low-power waveform by up to millions of times; the receiver detects and processes echoes at the microwatt level. In this article, we will examine transmitter-receiver technologies, from high-power amplifiers to waveform generators, from duplexers to different system architectures.

General Structure of the Transmitter-Receiver

Simplified block diagram:

Transmitter chain:

Waveform generator → Up-conversion → Amplification → Duplexer → Antenna

Receiver chain: Antenna → Duplexer → Filtering → Amplification → Down-conversion → A/D converter

Power levels change dramatically:

• Waveform generator: mV level

• Transmitter output: kW - MW

• Received echo: µW - mW

• Total dynamic range: ~90 dB

Transmitter-Receiver in the Radar Equation

SNR = (P_avg × G² × λ² × σ) / ((4π)³ × R⁴ × k × T_s × L × B)

Transmitter-receiver components:

• P_avg (average power): higher = better

• T_s (system noise temperature): lower = better

• L (losses): lower = better

Optimization of these parameters is the main goal of transmitter-receiver design.

High Power Amplifiers

Amplification is usually done in stages:

1. Driver amplifiers: watt level

2. Intermediate stages: hundreds of watts

3. Final stage (HPA): kilowatt - megawatt

Two basic topologies:

• Series: stages connected sequentially (single path)

• Parallel: multiple HPAs combined (more power, more complex)

Vacuum Tube Amplifiers

Type examples:

• Klystron: very high power (MW), narrow band

• Traveling wave tube (TWT): wide band, medium power (hundreds of kW)

• Crossed-field amplifier: compact, high efficiency

Characteristics:

• Very high peak power (MW)

• Low duty cycle (1-10%)

• High cost per unit ($300-500K)

• Large physical size

• Low cost per watt ($1-3)

Example: Millstone Radar

• 2 klystrons, L-band (1.3 GHz)

• 3 MW peak power, 120 kW average power

• Tube: 7 ft height, 600 lb weight, $400K cost

• 84 ft diameter parabolic antenna, 42 dB gain

Solid State Amplifiers

Characteristics:

• Low peak power (10-1000 W per module)

• High duty cycle (20-100%)

• Low cost per unit ($100-1000)

• Small physical size

• High cost per watt (in active arrays $50-100)

Example: PAVE PAWS

• 1792 active T/R modules

• 340 W peak power/module

• 75 ft diameter phased array

• >150,000 hours MTBF

Duplexer

The duplexer is a switch that provides critical isolation between the transmitter and receiver. Requirements:

• When transmitting: antenna connected to transmitter, receiver protected

• During reception: antenna connected to receiver, transmitter disconnected

• Isolation: ~90 dB (from MW to µW)

Additional limiter circuits are used for receiver protection - if a strong signal leaks into the receiver, the limiter cuts it to safe levels.

Waveform Generator and Frequency Conversion

The waveform generator creates the modulated signal transmitted by the radar. Generation at low frequency

(<100 MHz):

• More stable

• Cheaper

• Better control

Then, it is shifted to microwave frequency by up-conversion:

f_out = f_LO + f_IF (up-conversion)

f_IF = f_RF - f_LO (down-conversion)

Here, LO is local oscillator, IF is intermediate frequency, and RF is radio frequency.

Advantages of down-conversion:

• A/D converters offer better dynamic range at low frequency

• Digital processing is easier

• Lower cost

System Architectures

Dish Radar

Structure:

• Central transmitter (usually tube)

• Central receiver

• Connection to antenna via waveguide

• Mechanical scanning

Advantages:

• Lowest cost

• Simple design

• Easy frequency change

Disadvantages:

• Focused on a single target

• Slow scanning

• High waveguide losses

• Special transmitter required

Passive Phased Array

Structure:

• Central transmitter

• Ferrite phase shifters at each element

• Corporate feed network

Advantages:

• Beam agility (at µs level)

• Flexible resource management

Disadvantages:

• Feed network losses

• High power phase shifters required

• Higher cost than dish radar

Active Phased Array (AESA)

Structure:

• T/R module at each element

• Solid state amplifiers

• Distributed transmitter and receiver

Advantages:

• Low loss (amplifier at antenna)

• High reliability (graceful degradation)

• Beam agility and resource management

Disadvantages:

• Highest cost

• Complex cooling system

• Long design time

Digital Array

Advanced structure:

• In digital reception: A/D at each element

• In digital transmitter and receiver: waveform generation in T/R module

Advantages:

• Multiple simultaneous beamforming

• Full adaptive processing capability

• Maximum flexibility

Disadvantages:

• Highest computational requirement

• Highest complexity

• Emerging technology

Active T/R Module Structure

A typical T/R module:

• Low power input (from waveform generator)

• Driver amplifier

• High power amplifier (10-100W solid state)

• T/R switch (duplexer)

• Low noise amplifier (LNA)

• Phase shifter

• Control electronics

All these components are integrated into a small module (a few inches) and are supplied with cooling, power, and control lines.

Conclusion

Radar transmitters and receivers are critical subsystems that directly determine performance. Vacuum tube amplifiers provide very high power but are large, expensive, and have low duty cycles. Solid state amplifiers are compact and reliable but have high unit power cost. The duplexer must provide isolation between millions of watts and microwatts. Frequency conversion offers advantages of waveform generation and processing at low frequency. The choice of architecture—dish, passive array, active array, or digital array—involves fundamental trade-offs between cost, performance, and flexibility. Active and digital arrays stand out as the technologies of the future, but for certain applications, dish and passive arrays continue to be cost-effective solutions.

Radar Systems

Radar Systems9 - Tracking and Parameter Estimation in Radar Systems

After targets are detected, the radar system has two critical tasks: to make the best estimate of parameters (range, angle, velocity) and to form tracks by associating detections from scan to scan. These processes determine the operational value of the radar—enabling it to say not just "there is something there" but rather "the target is at this location, moving at this speed." In this article, we will examine parameter estimation techniques and tracking algorithms.

Estimated Parameters

Radar systems estimate the following parameters:

Position parameters:

• Azimuth and elevation angle (from antenna pointing direction)

• Range (from echo delay time)

• Radar cross section (in calibrated systems)

Motion parameters:

• Radial velocity (directly from Doppler)

• Radial acceleration (from change in velocity over time)

• Rotation and precession (for rigid bodies)

Parameter Estimation Accuracy

Basic estimation accuracy formulas:

Range accuracy:

σ_R ≈ c/(2B√(2×SNR))

Angle accuracy:

σ_θ ≈ θ_3dB/√(2×SNR)

Doppler velocity accuracy:

σ_v ≈ λ/(2T_coh√(2×SNR))

Here, B is bandwidth, θ_3dB is beamwidth, T_coh is coherent integration time, and SNR is signal-to-noise ratio. All accuracies improve proportionally to the square root of SNR.

Range Estimation

A target typically appears in multiple range samples. The matched filter output forms a peak around the true target position. The location of the largest output provides a coarse estimate, but for better accuracy:

• Curve fitting: least squares fit to the known matched filter response

• Weighted average: mean of sample positions weighted by amplitude

• Interpolation: parabolic interpolation between neighboring samplesWith these techniques, accuracy far beyond the range resolution can be achieved.

Angle Estimation Techniques

Sequential Lobing

The antenna is sequentially pointed in two directions—to the left and right of the target's estimated position. Echo amplitudes received from the two positions are compared. When the target is exactly in the center, the amplitudes are equal; otherwise, the difference indicates the direction toward the target.

Conical Scanning

The antenna beam is rotated around the estimated position of the target. Echo amplitude is modulated by the rotation angle:• Modulation phase → error direction• Modulation amplitude → error magnitudeWhen modulation is zero, the rotation axis is aligned with the target.

Monopulse

Monopulse is the most common and accurate method for angle estimation. Two or more receive beams are formed simultaneously and compared.

Amplitude comparison monopulse:

• Four separate feeds (or array quadrants) are used

• Sum (Σ) and difference (Δ) signals are formed

• Azimuth difference: (A+B) - (C+D)

• Elevation difference: (A+C) - (B+D)

Error signal:

ε = |Δ/Σ| × cos(φ_Δ-Σ)

Here, φ_Δ-Σ is the phase difference between the sum and difference signals. ε linearly indicates how far the target is from the antenna boresight.

Phase comparison monopulse:

• Two separate antennas are used

• The same wavefront reaches both antennas

• Path difference: d×sin(θ)

• Phase difference: 2π×d×sin(θ)/λ

The angle is calculated from the phase difference.

Accuracy, Precision, and Resolution

These three concepts have different meanings:

• Accuracy: Degree to which measurements conform to the true value

• Precision: Repeatability of measurements (low random error)

• Resolution: Ability to distinguish two targets

A system may have high precision (consistent measurements) but low accuracy (systematic error/bias). Resolution is determined by beamwidth, pulse width, and Doppler filter width.

Tracking Algorithms

Tracking is the process of associating successive detections with the same physical object. Basic steps:

1. Detection reports are received

2. Association with existing tracks is attempted (priority)

3. For unassociated detections, a new track is initiated

4. Future position is predicted for updated tracks

5. Tracks without data are "coasted" or terminated

Association is performed using a "search gate" placed around the predicted position.

Gate size:

• Prediction error

• Measurement error

• Possible amount of maneuver

are used to determine it. Detections falling within the gate are track candidates.

Track Filtering

Alpha-Beta tracker:

A simple tracker uses separate gains for position and velocity:

x̂_k = x̂_k|k-1 + α(z_k - x̂_k|k-1)

v̂_k = v̂_k-1 + (β/T)(z_k - x̂_k|k-1)

Kalman filter:

An optimal method calculates dynamic gains by considering the covariances of measurement and process noise. It provides more complex but more accurate estimates, especially for maneuvering targets.

Track-Before-Detect (TBD)

In the conventional approach, a detection threshold is applied first, then tracking is performed. In TBD:

• Data from many scans are stored in memory

• All possible trajectories are tried

• Kinematically meaningful trajectories are sought

• The correct trajectory produces consistent tracks over many scans

Advantages:

• A higher false alarm rate per scan can be tolerated

• Lower SNR targets can be detected

Disadvantages:

• Requires very intensive computation

• There is a delay between detection and notification

Tracking with Phased Array Radars

Phased array antennas provide significant advantages for tracking:

• High update rate (milliseconds)

• Ability to observe many targets simultaneously

• Flexible resource management

Instead of feedback control loops, computer-controlled resource allocation is used. This enables simultaneous execution of surveillance and tracking functions.

Limitations and Errors

Real-world limitations:

• Receiver noise: increases estimation variance

• Calibration errors: create systematic bias

• Target glint: angle noise in complex targets

• Multiple targets: monopulse distortion

• Multipath propagation: bias in low-angle tracking

Angle glint is particularly problematic—phase interference between different scatterers of a complex target can cause the target to appear beyond its physical boundaries.

Conclusion

Parameter estimation and tracking are critical processes that convert the radar's raw detections into usable target information. Monopulse techniques provide angle accuracy well below the beamwidth. Tracking algorithms associate detections from scan to scan and predict target trajectories. Phased array radars offer superior tracking performance thanks to beam agility. Advanced techniques such as TBD enable detection of lower SNR targets at the cost of computational expense. Together, these capabilities determine the tactical value of modern radar systems.